Military Mics Are Now Being Fitted On Soldiers’ Teeth

Say hello to this magic military invention, a tiny tooth microphone that enables covert agents to communicate without a (visible) trace. The microphones – aptly dubbed Molar Mics – are clipped onto soldier’s back teeth, enabling state-of-the-art wireless communication on duty.

As with any nascent technology, it’s not yet plain sailing; the human brain requires time to adapt – about three weeks – before optimal audio processing takes place. That being said, audio is perceptible from the get go, as Peter Hadrovic, CEO of Sonitus Technologies, the device’s parent company, explained to

Defense One.

“Over the period of three weeks, your brain adapts and it enhances your ability to process the audio,” said Hadrovic. But even “out of the gate, you can understand it,” he assured.

Given the heavily concealed location of the the mics, there’s no need to stress about a conspicuous external microphone giving the game away. Sonitus’s

website expounds the Molar Mics’ capacity for wireless communication, eliminating the need for “ear pieces, microphones and wires on the head”.

Rather, sound is input via the users’ jawbone, skull and auditory nerves, with outgoing sound travelling via a radio transmitter on soldiers’ necks. The noise will then travel to an external radio unit manned by the operator. Signal can then be transmitted at the operator’s discretion. It’s being

billed as a “new audio path “supersense” for wireless communication”.

If this all sounds a little alien, it needn’t; it’s the same premise as listening, but instead of using your ear canals, you’re using your bones. “Essentially, what you are doing is receiving the same type of auditory information that you receive from your ear, except that you are using a new auditory pathway — through your tooth, through your cranial bones — to that auditory nerve,” explains Hadrovic. “You can hear through your head as if you were hearing through your ear.”

This is no gimmick, with reports that the US Pentagon – the nucleus of American national defence – has signed a $10 million contract (£7.7 million) the California-based company. Nor is this the company’s first involvement with the US government; Sonitus was the beneficiary of early funding from In-Q-Tel, a nonprofit investment firm which supplies the CIA with the latest information technology.

The Military Now Has Tooth Mics For Invisible, Hands-Free Radio Calls

The future of battlefield communications is resting comfortably near your back gums.

Next time you pass someone on the street who appears to be talking to themselves, they may literally have voices inside their head…and be a highly trained soldier on a dangerous mission. The Pentagon has inked a roughly $10 million contract with a California company to provide secure communication gear that’s essentially invisible.

Dubbed the Molar Mic, it’s a small device that clips to your back teeth. The device is both microphone and “speaker,” allowing the wearer to transmit without any conspicuous external microphone and receive with no visible headset or earpiece. Incoming sound is transmitted through the wearer’s bone matter in the jaw and skull to the auditory nerves; outgoing sound is sent to a radio transmitter on the neck, and sent to another radio unit that can be concealed on the operator. From there, the signal can be sent anywhere.

“Essentially, what you are doing is receiving the same type of auditory information that you receive from your ear, except that you are using a new auditory pathway — through your tooth, through your cranial bones — to that auditory nerve. You can hear through your head as if you were hearing through your ear,” said Peter Hadrovic, CEO of Molar Mic creator

Sonitus Technologies. He likened the experience to what happens when you eat a crunchy breakfast cereal — but instead of hearing that loud (

delightfully marketable) chewing noise, you’re receiving important communications from your operations team.

Your ability to understand conversations transmitted through bone improves with practice. “Over the period of three weeks, your brain adapts and it enhances your ability to process the audio,” said Hadrovic. But even “out of the gate, you can understand it,” he said. (more below)

The Molar Mic connects to its transmitter via

near-field magnetic induction. It’s similar to Bluetooth, encryptable, but more difficult to detect and able to pass through water.

Sonitus received early funding from

In-Q-Tel, the nonprofit investment arm of the CIA, to develop the concept. Hadrovic declined to say whether CIA operatives had used the device in intelligence gathering. But the Molar Mic has seen the dust of Afghanistan and even played a role in rescue operations in the United States.

In Aug, 2016, a connection Hadrovic met through In-Q-Tel introduced the company to the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental, or DIUx (since rebranded simply DIU). They linked Sonitus to their “warrior in residence” and several other

pararescuemen, or PJs, from the Air National Guard’s 131st Rescue Squadron at Moffett Field in Mountain View, California, near the DIU headquarters. Pararescuemen airdrop behind enemy lines to rescue downed aircrews.

A few of the airmen took prototypes of the device on deployment to Afghanistan. Although they didn’t use it during missions, they were able to test it repeatedly and offer feedback. Hadrovic said the 14 months of testing were critical to improving the product for use by the military.

In 2017, a few of the PJs from the 131st brought Molar Mic along when they deployed to Texas to help with rescue operations for Hurricane Harvey. Hadrovic said the airmen were pleased with its performance during complicated operations involving water, helicopters, and a lot of external noise.

“This guy is standing in neck-deep water, trying to hoist a civilian up into a helicopter above. He says, ‘There is no way I would be able to communicate with the crew chief and the pilot if I was not wearing your product.’” (More below)

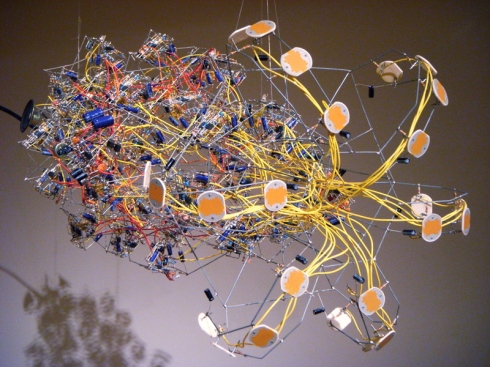

A graph illustrating the communications network of the “Molar Mic” from Sonitus.

The same technology holds the potential for far more rich biometric communication between operators and their commanders, allowing soldiers in the field and their team to get a timely sense of how the soldier is responding to pressure or injury, without him or her having to communicate all of that explicitly. It’s something that the military

is working toward.

“As we look to the future human-machine interface… the human creates a lot of information, some of it intentional, some of it unintentional. Speaking is one form of information creation,” says Hadrovic. “Once you’ve made something digital, the information can be interspersed...We have a tremendous wealth of opportunities to communicate out of the person and back to the person, information that can be either collected from them and processed offline and given back in a nice feedback loop. What we’ve done is invested in the platform that will support these future elements.”

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/39/1c/391c4ba0-41a9-4dad-bbc5-ef30f00b2fa5/manchurian-mama.png)